- Home

- Ghalib Lakhnavi

The Adventures of Amir Hamza Page 2

The Adventures of Amir Hamza Read online

Page 2

While sadly lacking in lock-picking skills at the time, we had not entirely wasted our time at school. Here was an opportunity to put our book learning to use. It was the principle of the lever that we applied—inserting a heavy shish-kebab skewer between the lid and the top of the trunk and giving it a little lift. The physics were flawless. The lid rose, then twisted, becoming almost dog-eared. Sliding our hands in and grabbing a book each was what we did next, before covering the lid with an old quilt and stealing away.

Our parents never suspected we had burglarized the iron chest. It was a little unimaginable for two quiet boys living a protected life to have committed such a heinous deed (may that be a lesson for parents not to put a limit on their children’s imaginations). In that trunk, among other books, was the juvenile edition of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza, in a set of some eight or ten books. That was my first introduction to the devs, jinns, peris, cow-footed creatures, horse-headed beasts, and elephant-eared folks.

I remember that after spending an hour or two reading these stories my brother and I would undergo a transformation. One of us would become Amir Hamza, the other the king of India, Landhoor bin Saadan, or some other such mighty champion. We would head for the courtyard. Our arms and armor were ready and we would gird ourselves: swords improvised of hockey sticks, spears made of bamboo, body armor fashioned of sofa cushions. Mattresses would be spread on the courtyard floor to break the fall, and hostilities were declared. Once we tired of fighting with weapons, it would be time to wrestle. When that too was insufficient to dissipate the adrenaline rush, our focus would turn to the lizards. While our parents slept, Amir Hamza and Landhoor would indulge in the pleasures of the chase. Death to the infidel lizards and the faithless chameleons!

Meanwhile, at school I was having an existential crisis—or perhaps it was one of the spiritual kind. Often during the classes I would have an unworldly awakening. I would look around and find myself surrounded by uniformed creatures sitting in rows while an older person chalked something on a blackboard. I would try but could never figure out how I had ended up with them. I would have preferred to be a dev, running around swinging a tree trunk and clobbering humans with it. Or a jinn, throwing humans from the heavens into the mountains and seas. Thus, at a young age I had my first experience of alienation. I returned home worn, exhausted, and a little stupider, and sneaked away to the storage room where my real and true friends awaited me—the devs, jinns, and so forth. I felt one with them. In their company I never had any of my spiritual or existential dilemmas. I was back under the covers with bound paper and a pencil light. This time I took care not to be caught. And so the years passed.

Let me now fast-forward six years, to a time when I was having another crisis. I had ruined my eyes from reading with the pencil light and disqualified myself from my natural calling as a soldier. Then I had moved to Karachi and ended up in the electrical engineering program, where both the induction motor and the synchronous motor refused to reveal their secrets to me. I decided not to force the issue. But my parents were not prepared to hear of my dropping out. So I carried on, going in the morning to the university, where some considerate person had provided very comfortable sofas in the dining lounge. While the future builders of the country made their parents proud and strove mightily against the curriculum in rooms adjacent, a lonely truant grappled with his very own curriculum of assorted fiction scrounged from secondhand bookshops.

Most of the books I read at that time were in English, many of them classics. A story is a story, and I was too busy enjoying the books to pause and wonder where all the classics of the Urdu language were hiding. One did not see them in the bookstores.

After dropping out of engineering studies in the late 1980s, I spent a few years experimenting with learning languages, working as a journalist, and making films—and failing at all of them. During this time, I also made new friends who introduced me to good contemporary Urdu fiction. However, the fiction writers were unable to keep pace with my reading consumption and I soon ran out of Urdu books. In their absence I read in English, and later, when I tried to write fiction myself, I found it easier to structure sentences in English than in Urdu. Still, for a very long time, I needed to read something in Urdu before I could go to sleep.

Then I got married, and in 1994 I moved to Toronto. One day at the University of Toronto library I came across Urdu Ki Nasri Dastanen. It was a record of Urdu’s classical literature compiled by Gyan Chand Jain. It contained information about a large number of classics written in the Urdu language in the nineteenth century and earlier. Most of this literature had originated in the oral narrative genres of dastan and qissa. They were packed with occult, magic, and sorcery. I realized that if I could find them, I would have more than a lifetime’s supply of reading.

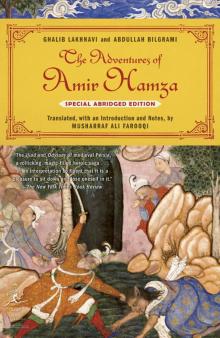

I also discovered the Dastan-e Amir Hamza a second time. I learned of one version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza (1883–1917) that existed in forty-six volumes, each of them approximately a thousand pages long. It can no longer be found and exists only in one or two special collections in the form of microfilm. Another version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza (1801) was compiled by Khalil Ali Khan Ashk. It was one of the many texts written at the Fort William College in Calcutta to teach Urdu to the officers of the British colonial administration. I obtained an undated reprint of this book but found Ashk’s language rather insipid. It also lacked a large portion of Amir Hamza’s adventures in Qaf. This Ashk fellow was probably some freedom fighter who had infiltrated the Fort William College to sabotage the education of the colonial officers. He must have feared that if the Brits began enjoying these stories too much they might become very difficult to get rid of. I could appreciate his motives, but I did not appreciate the fact that in the process he had also killed many of my friends. That was just not right. Finally, I discovered the most popular one-volume version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza, first published by Ghalib Lakhnavi in 1855 and amended by Abdullah Bilgrami in 1871. Neither one of them were “authors” in the sense we understand today. They were compilers of this oral dastan, and in the process they rewrote and expanded the story.

When I started reading about the Dastan-e Amir Hamza in greater detail, I also discovered a family connection to its social history. My great-grand-uncle Ashraf Ali Thanvi (1864–1943) was a religious scholar and one of the spiritual leaders of the Indian Muslims. He found the story’s ribald passages unsuitable for the sensibilities of proper women and in his book Bahishti Zevar, which is an introduction to social norms for women, he declared that they should avoid reading it. Now that I have read these passages, I have the same advice for proper women. Taking modern-day sensibilities into account, I would just add that men, too, must not sit down with this book without a bottle of smelling salts close at hand.

Through the writings of dastan scholar Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, I began to understand the significance of this legend, its complex theme of predestination and its thousand-year history in the South Asian subcontinent. At first, while reading the Lakhnavi-Bilgrami Dastan-e Amir Hamza, I had difficulty understanding the ornate passages. I had to look into classical dictionaries to understand what was being said. Three generations ago, those considered truly literate in our culture could read and write with equal facility in Arabic, Persian, and Urdu. My father’s generation had lost Arabic and the ability to write in Persian. In my generation, reading classical Urdu had become an issue, too. With our literary heritage becoming inaccessible to us at this rate, it seemed reasonable to assume that—let alone being able to share it with other cultures—we would soon find ourselves alien to it.

This was a complex and weighty problem that lay far beyond my capacities to resolve. I worried about my friends—the devs, the cow-footed creatures, the horse-headed beasts, the elephant-eared folks. If the world ever forgot their existence I knew I would not be able to bear the tragedy.

I checked to see if the Dastan-e Amir Hamza had ever been translated into English or one of the European languages. I found out that in 1892, S

heik Sajjad Hosain published an abridgement of Book One titled The Amir Hamza: An Oriental Novel. By his own admission he tried to make a novel of it, but the results were disappointing, the experiment was left unfinished, and he was not heard from again. In 1895 Ph. S. Van Ronkel published his Dutch study of Amir Hamza’s legend, titled De Roman van Amir Hamza. Then, in 1991, Frances Pritchett published The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah, which contained excerpts translated from a 1969 edition. That was it. The complete Dastan-e Amir Hamza had never been translated into English or any other Western language.

Someone simply had to be found who had enough time on his hands to translate a thousand-page book. Ideally, this person should not be bright enough to anticipate the distinct likelihood that the book might never be published. As the whole thing was to be done without any grant money, it also had to be someone whose spouse had a reliable job. Since everyone I knew seemed to have a purpose in life, and their spouses would not hear of any such nonsense, the search soon drew to a close. And the matter would have rested there but for a most eventful dream, which should be recounted here in its entirety due to its historic significance.

It was a wintry night. I was fast asleep when suddenly I heard galloping noises and woke up. A horse-headed creature appeared from the darkness. Behind him walked an elephant-eared lady carrying a candle. The horse-headed gent greeted me with a sly smile, congratulated me, and said that I had been chosen to do the translation. Then the elephant-eared lady came forward and said that everyone was counting on me. Before I could say anything or ask any questions, they plunged back into darkness. I heard sniggering, galloping sounds, and then all was quiet.

It is not every day that one receives such distinguished visitors in dreams and is declared their chosen one. Naturally, I could not forget the dream. And didn’t the lady tell me that everyone was counting on me? I could not ignore that, for sure. I finally told my wife what the horse-headed gent and the elephant-eared lady expected of her, and threw myself wholeheartedly into the task.

I had thought that with such auspicious beginnings the translation itself would be a breeze. But I ran into major problems with the very first passage. It took me several hours and left me somewhat disillusioned and embittered. I persevered and tried not to think too much about the meaning of my dream visitor’s sly smile. After Book One the language becomes simpler, the ornate passages shorter, and the poetry less frequent. I also had more practice. A few years earlier, I had translated the Urdu poetry and fables of Afzal Ahmed Syed. This exposure to translating one of our contemporary masters helped me. But I think the real breakthrough came when I learned to keep three fat dictionaries open in my lap at the same time.

Because I visited the text over and over again, the structure of the tale began to reveal itself. I was happy that I was beginning to see structure in fiction, but I could not say the same about my life. I was piling up rejection slips for my own writings. Naturally, I felt jealous of Ghalib Lakhnavi and Abdullah Bilgrami, who had found publishers in their time and were important enough to be translated. The evil thought often crossed my mind to stop the translation. That would teach Messrs. Lakhnavi and Bilgrami a nice lesson! But my friends began calling to inquire when the book would be ready. For the last few years I had constantly bragged to them about it, and they had remembered. Now I had to finish it just to save face. Later, when the Modern Library decided to publish it, it became a contractual obligation as well. In short, as always I was caught in a web of my own follies, and the only way out was to finish the thing.

Now that the translation is done, after seven years of intermittent work, I hope that everyone is satisfied. If they feel a need to express their gratitude I would very much prefer it if they did not appear in my dreams and communicated instead by e-mail.

I also have a message for all young boys and girls. They should take warning from my example and get themselves a good education. I now realize its virtues. If I had had one, the horse-headed fellow and the elephant-eared lady could not possibly have made such a capital fool out of me.

—Toronto, July 3, 2007

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

In 1855, the obscure press Matba-e Hakim Sahib in the Indian city of Calcutta published a book titled Tarjuma-e Dastan-e Sahibqiran Giti-sitan Aal-e Paighambar-e Aakhiruz Zaman Amir Hamza bin Abdul-Muttalib bin Hashim bin Abdul Munaf (A Translation of the Adventures of the Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction, the World Conqueror, Uncle of the Last Prophet of the Times, Amir Hamza Son of Abdul Muttalib Son of Hashim Son of Abdul Munaf).1 Its writer, Navab Mirza Aman Ali Khan Bahadur Ghalib Lakhnavi, identified himself as the son-in-law of Prince Fatah Haider, the oldest son of Sultan Tipu of Mysore. According to one account, the writer was a new convert to Islam and a public official.2

This book by Navab Mirza Aman Ali Khan Bahadur Ghalib Lakhnavi (Ghalib Lakhnavi, for short) was one of the earlier versions of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza (Adventures of Amir Hamza) printed in India in the Urdu language. It already existed in multiple handwritten manuscripts and was a long-established legend in the South Asian oral narrative tradition of dastan-goi (dastan narration). It was a narrative of composite authorship, and different versions of the same event existed in different narrative traditions.

Ghalib Lakhnavi’s use of the term “translation” is confusing. Unless it was a translation from a Persian-language version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza originally composed in South Asia, it is difficult to explain the overwhelming number of references particular to the social life and culture of South Asia found in the book. Certain passages which are in regional Indian dialect could not possibly have originated in any foreign language. It is more probable that Ghalib Lakhnavi compiled the text from various versions and attributed it to an older source to give his story an ancient pedigree, a practice common among dastan writers.

Ghalib Lakhnavi’s text became the basis of a very popular edition that remained in print until recently, although these later editions were drastically abridged. In November 1871, sixteen years after Ghalib Lakhnavi published the book, the Naval Kishore Press in Lucknow brought out its own version of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza.3 The book was identified as an amended version of a tale previously published in Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, and Lucknow.4 However, the author of the text of the Naval Kishore Press version was not acknowledged, only the man who amended it: Abdullah Bilgrami, an instructor of the Arabic language in Kanpur. We now know that it was, in fact, Ghalib Lakhnavi’s text, modified by Abdullah Bilgrami by adding ornate passages and poetry to it. This translation is made from Abdullah Bilgrami’s 1871 edition of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza.

The oral narrative tradition of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza heavily influenced its written version. The text of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza was used both for reading and as a guide for the narrator of the dastan. In a few places, instructions appear to guide the person narrating the story. A dastan narrator knew more than one version of a particular episode of the dastan and used the one most suited for the audience being addressed. In addition, a dastan was never narrated in its entirety during a session. Only certain episodes from it were narrated. Therefore, considerations of continuity and structural integrity were not important. The histories of multiple versions of the same event and the loosely woven oral tradition sometimes intervene in the text. In some places parallel traditions and discrepancies have crept in (see notes 13 and 14 to Book Two, notes 5, 6, and 8 to Book Three, and notes 12, 13, and 18 to Book Four).

I have not tried to straighten out these inconsistencies, not only because to do so would compromise the story, but also because they allow for a comparison of different traditions and texts, which can be very helpful in the study of the dastan genre. These inconsistencies reveal that this text was compiled using at least three variant traditions (see note 13 to Book Two, note 6 to Book Three, and note 18 to Book Four).

Consistent with the classical dastan literature, the Urdu text of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza is unpunctuated and has no

text breaks except where a new chapter is marked. While this offers a translator great flexibility in structuring a sentence, it is a challenge to identify and isolate individual phrases and sentences in a continuous text before translating them. In some instances, the print was not legible and an approximation was made in choosing the missing text. Such instances have been marked with a question mark following in brackets.

The title amir (meaning “commander” or “leader”) has become an inseparable part of the hero’s name and has been used as such throughout the text. The title khusrau (meaning “king”) has likewise become part of Landhoor’s name and is similarly used.

The characters and the numerous legendary kings, warriors, sorcerers, historical figures, deities, and mythical beings mentioned in the story are grouped together in the List of Characters, Historic Figures, Deities, and Mythical Beings.

NOTES

1. The Library of Congress has a microfiche of this title (Control Number: 85908676; Call Number: Microfiche 85/61479 [P] So. Asia).

2. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Sahiri, Shahi, Sahibqirani: Dastan-e Amir Hamza ka Mutalaa, Volume I, Nazari Mubahis (New Delhi: National Council for the Promotion of Urdu Language, 1999), 209.

3. The only known copy of this text is in the British Library (Reference No. 306.24.B.21).

4. Dastan-e Amir Hamza Sahibqiran (Lucknow, India: Naval Kishore Press, 1871), 752.

The Adventures of Amir Hamza

The Adventures of Amir Hamza